How Did Workers Respond To The Changing Demands Of The Workplace In The Late Nineteenth Century?

Introduction

The Us experienced extraordinary social and economic change between the terminate of Reconstruction and the kickoff of Globe State of war I. In 1870, only one-quarter of Americans lived in cities. By 1920, over 1-one-half did. The metropolis of Chicago grew from a population of 298,977 in 1870 to over 2.7 million in 1920. This process of urbanization was inseparable from ii other areas of enormous change: industrialization and immigration. Technological advances, particularly in the making of steel, allowed the construction of large factories for mass production. Big-scale, well-financed companies came to boss nearly industries. With these changes in the scale and system of industry came meaning changes in workers' opportunities and experiences. Factories no longer needed many skilled artisans or craftsmen, whose work could now be done by machine. Instead, they needed numbers of unskilled or semiskilled workers to operate the machines. Many of these workers were recent arrivals from abroad. Between 1880 and 1920, more 23 million immigrants came to the Us. Before generations had arrived primarily from Northern and Western Europe. But, past the 1900s, the great majority came from Eastern and Southern Europe, including Jews, Italians, Czechs, Russians, and Poles.

Many of the demands made by industrial workers in the 1870s—for example, for an 8-60 minutes workday—were non fulfilled until Earth War I, or even the 1930s.

Industrialization, immigration, and urbanization became new sources of social disharmonize and instability. Industrial workers who experienced dangerous or exploitative weather condition had little leverage to negotiate off-white wages or workplace protections. New immigrants often faced suspicion and hostility from Anglo-Americans and older immigrants. Cities struggled to see the demands that such rapid growth placed on housing, transportation, water, and sewage systems.

Traditionally, historians have divided this catamenia from 1877 to 1919 into ii, contrasting eras: the Gilded Age of the late nineteenth century and the Progressive Era of the early twentieth century. In this model, the Gilded Age produced the issues—related to economic inequality, industrialization, urbanization, and immigration—that the Progressive Era attempted to solve through social reform and legislation. But many historians now argue that the issues that emerge in the 1870s continue through the 1910s, every bit did efforts to contend with them. Labor historians, in detail, find that many of the demands fabricated by industrial workers in the 1870s—for example, for an eight-hour workday—were non fulfilled until World State of war I, or even the 1930s. The documents that follow therefore span the "long Gilded Age" to portray working conditions, workers' organizations, and demonstrations in Chicago from the Haymarket Thing in 1886 to the reform campaigns of the 1910s.

Please consider the post-obit questions as you review the documents

- What were working conditions like in Chicago during the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-centuries?

- What demands did workers make during this period? What kinds of organizations did they form? How did these demands and organizations change over time? What were the successes and failures of workers' organizations?

- How did industries—and the public—respond to workers' demands? How did the media portray workers, their organizations, and their leaders?

The Labor Movement and the Haymarket Affair

Nineteenth-century employers often expected workers to spend 12 to 14 hours a twenty-four hour period, 6 days a week on the job. In the 1880s, workers' organizations, led by the Knights of Labor, joined with political radicals and reformers to organize a national attempt to need an eight-60 minutes workday. During the first week of May 1886, 35,000 Chicago workers walked off of their jobs in massive strikes to protestation their lengthy work weeks. Some of these strikes involved vehement skirmishes with the police. At least two strikers were killed on May iii. In response, the next evening, roughly 1,500 people gathered at the W Randolph Street Haymarket, a market place on the edge of the urban center where people bought hay for their horses. Although the May 4 rally featured fiery speeches from political radicals and labor leaders, it was a peaceful gathering. As the rally drew to a close, hundreds of policemen moved in to disperse the crowd. Someone threw a bomb at the police brigade, killing one officer instantly. The police responded with a barrage of bullets. An unknown number of demonstrators were killed or wounded. Lx police officers were injured and eight eventually died. Politicians and the press blamed radicals for the violence. Although there was no evidence linking specific people to the flop, 8 men were convicted of murder on the basis of their political writings and speeches. Four men were executed; one committed suicide. The trial was later considered grossly unjust and, in 1893, the Illinois governor granted absolute pardon to the three, remaining imprisoned defendants. The labor organizations, withal, were severely damaged. The documents in this section include the Knights of Labor's statement of principles, a broadside advertising the Haymarket rally (pictured in the Introduction), and the May fifteen, 1886, encompass of Harper's Weekly, a national political mag.

Selection: The Knights of Labor Illustrated, "Declaration of Principles," 7-9 (1886).

Questions to Consider

- What are the principles and goals of the Knights of Labor, as outlined in this document? Which, if any, of their goals do you consider reasonable? Which, if any, do you consider unreasonable?

- Examine the broadside advert the Haymarket rally. What tin yous larn about the rally'south audience and purpose from this broadside?

- Examine the Harper'southward cover illustration from the week following the Haymarket demonstration. The full title reads: "Too Heavy a Load for the Trades-Unions. The Competent Workman Must Back up the Incompetent." The label "Agitators" appears on the sleeve of the homo conveying the whip. What is the illustrator'south interpretation of the workers' strikes and demonstrations?

Wages and Nationalities in a Chicago Neighborhood

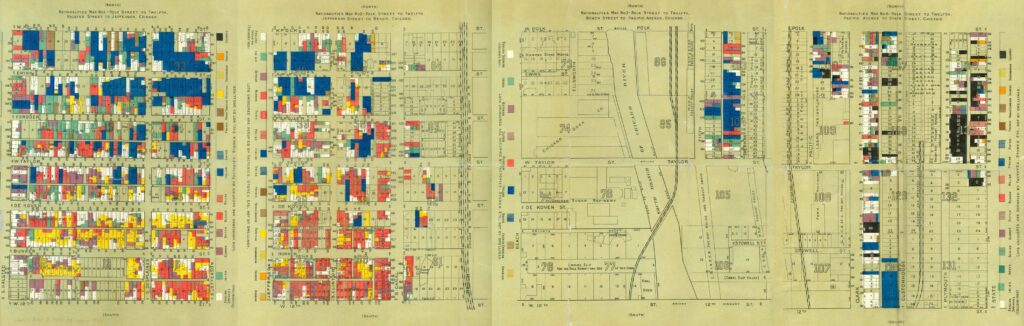

Samuel Sewell Greeley's Wage Map and Nationalities Map were published past Hull House in 1895 equally role of a project to document and describe how people lived and worked in Chicago's poorest neighborhoods. Hull House was a settlement house established in Chicago'south Near Due west Side slum as office of a motility to redress the widening gulf between the poor and the affluent in America'due south cities. Center-class women and men lived at Hull House and provided services, classes, and organizational support to people in the neighborhood. In order to assemble information to create the maps, staff from Hull Firm and the federal Agency of Labor went through the neighborhood business firm by house and asked residents about their indigenous origins, their work and wages, and the number of people in their households.

Questions to Consider

- Examine the Wage Map closely. (Note: Weekly household earning of $5.00 in 1890 is approximately equivalent to $124.00 in 2010. 20 dollars in 1890 is comparable to $494.00 in 2010.) What conclusions can yous draw virtually the economic status of the people who lived in this neighborhood? What patterns practise y'all notice in the locations of each income group?

- Examine the Nationalities Map closely. Which ethnicities and races are represented here and in what proportions? (Please notation: Bohemian refers to people now known as Czech.) What criteria were used to define each group? On what basis exercise y'all think the map's creator decided which colour to assign each group?

- What patterns do you discover in the distribution of specific indigenous groups throughout the neighborhood? Are groups evenly dispersed? What do y'all observe surprising about the neighborhood's limerick?

- Consider the two maps together. What patterns practise yous come across? Do wages and nationalities correspond in any ways?

The Pullman Strike

In 1867 George Pullman founded the Pullman Palace Car Visitor to manufacture passenger bus railroad cars and, by the end of the century, he had monopolized the industry. Company headquarters moved to the outskirts of Chicago in 1880, where Pullman congenital a big manufacturing plant and a company town with his name. Past the 1890s, half-dozen,000 of his fourteen,000 nationwide employees were based in Pullman, Illinois. Pullman was initially hailed every bit a forward-thinking industrialist, who provided a loftier quality of life for his workers. But, when the national economy took a downturn in 1893, the company laid off thousands of employees and cut wages. Pullman would non negotiate with the workers, who so went on strike in May 1894. The American Railway Matrimony (ARU) threw its support behind the Pullman strikers by initiating a national cold-shoulder of the Pullman Company. ARU members refused to work on any railroad train carrying a Pullman car, crippling railway traffic across the country. The federal authorities, nether President Grover Cleveland, intervened in the crisis, first, by requesting a courtroom injunction forbidding the cold-shoulder and, then, past sending soldiers to Chicago and elsewhere to enforce the injunction. The ARU's leader, Eugene V. Debs, was arrested and imprisoned for promoting the boycott. By mid-July, both the strike and the wedlock had been broken, only not without considerable violence. Pullman himself came under widespread criticism for underpaying his workers and refusing to negotiate. The documents in this department include representations of and responses to Pullman, Debs, and the strikers.

Questions to Consider

- Examine the drawings of the "Burning of Half dozen Hundred Freight-Cars" and "The Great Chicago Strike," which appeared in unlike publications. What is happening in these scenes? How do demonstrators and soldiers appear in the images?

- Consider the two Harper's Weekly covers representing Debs and the strikers. How do these illustrations portray Debs? Do they encourage sympathy for Pullman or for ARU workers? On what grounds do they criticize Debs and other labor organizers?

- What is the stance taken by the final, editorial cartoon from the Chicago Herald? On what grounds does it seem to criticize George Pullman?

Conditions in the Meatpacking Industry

Upton Sinclair'due south 1906 novel, The Jungle, exposed the roughshod working conditions and horrifying nutrient processing system of Chicago's meatpacking industry. Information technology as well revealed the metropolis'southward pervasive civilization of corporate and political corruption and the systemic exploitation of industrial workers, particularly recent immigrants. President Theodore Roosevelt embraced Sinclair's critique of the industry and used the novel's public affect to push through Congress the Pure Nutrient and Drug Act and Meat Inspection Deed later that year.

Choice: Upton Sinclair, The Jungle, 44-45, 116-117 (1906).

Questions to Consider

- How would you characterize the process of slaughtering and processing cattle as it is represented in the beginning extract here? What are the advantages of such a system? What could be the disadvantages?

- Consider the account of the factory in the second excerpt. What are some of the dangers to the workers and, implicitly, to consumers that Sinclair catalogs here? What is the cause of these unsafe conditions?

- Consider the two passages together. In what ways does the 2nd business relationship crusade you to re-evaluate the first? Does the first business relationship contain indicators that might lead yous to suspect the bug illustrated in the second account?

The Garment Workers' Strike

Betwixt 1880 and 1920, twenty pct of women over the age of x joined the paid labor forcefulness. In cities like New York and Chicago, a significant portion of these women worked in the garment industry every bit dressmakers and embroiderers. (Men worked in the garment industry as well, primarily as cloakmakers, cutters, and pressers, trades which were thought to require greater skill or the handling of heavy equipment.) Many of these women were recent immigrants who worked in sweatshops, cramped, poorly lit workplaces, ofttimes prepare in tenement buildings. Sweatshop owners supplied material to larger factories. Women across the industry were grossly underpaid, whether they worked in pocket-sized shops or big factories. Their wages could be every bit low as $iii.00 per week for 60 to 84 hours of work. Garment workers were among the first women to grade unions.

Selection: The International Socialist Review, "The Garment Workers' Strike," 260-264 (1915).

Questions to Consider

- How does the article portray weather in the garment industry? What do the strikers promise to achieve?

- How did the city and, specifically, Chicago police respond to the protestation?

- Examine the images that accompany the article. How practise they portray the workers and their demonstration?

Two Approaches to Organizing Labor

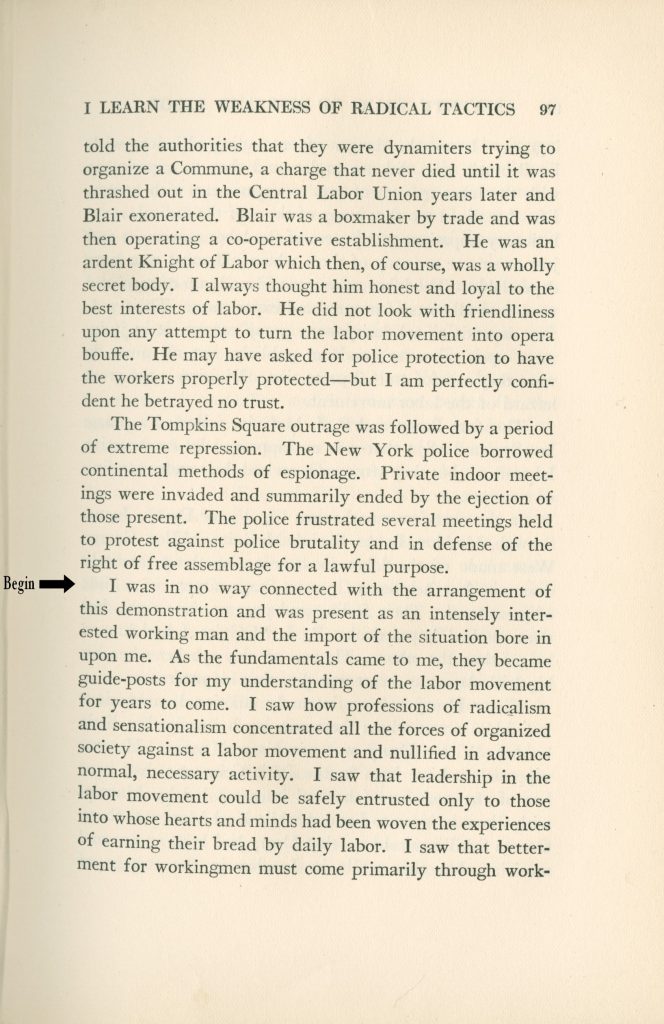

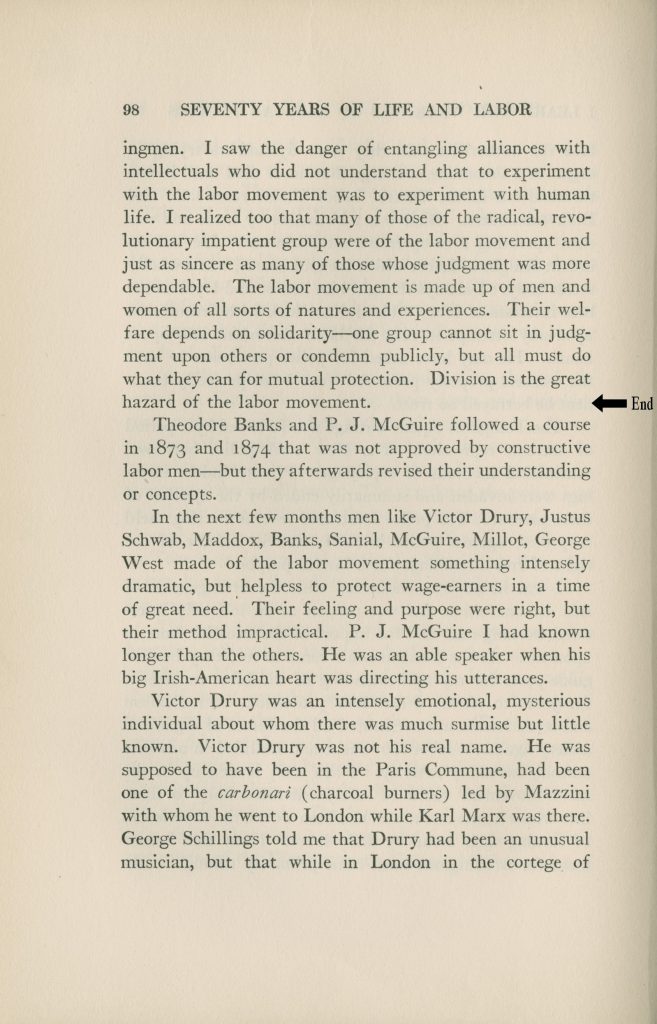

Eugene 5. Debs and Samuel Gompers both emerged as of import labor leaders in the late nineteenth century. Past the 1900s, all the same, they had come to strikingly different conclusions nearly what the goals and methods of the labor movement should be. Debs began working in the railroad yards as a teenager, became involved in workers' organizations and, in 1893, formed the American Railway Spousal relationship. He went on to institute the Chicago-based, radical labor system, the International Workers of the World (IWW), and to run—five times—for president of the United states as the candidate of the Socialist Party of America. He was sharply critical of capitalism and believed that economic resource should non exist owned by individuals or private companies, but should belong to anybody. Debs opposed U.S. entry into World War I on the grounds that workingmen'southward lives should non be sacrificed for rich men'south interests, and spent 3 years in prison for a spoken communication urging resistance to the draft. Like Debs, Samuel Gompers came from a working class family. He was the son of a cigar maker and began working in his father's shop at thirteen. He rose quickly to go a local, and so a national union leader, and, in 1886, to plant the American Federation of Labor. His philosophy of labor organizing was shaped by this early on experience with skilled craftsmen. While Debs urged workers to unite as a class, skilled and unskilled together, Gompers believed workers should form unions based on their specific trades. For example, under his approach, construction workers would not form a single wedlock, instead they would organize according to their various trades, as painters, carpenters, and plasterers. Each group would then deal independently with employers. Critics argued that Gompers' approach excluded unskilled workers from unions and immune employers to pit unions confronting each other. Notwithstanding, Gompers defended his methods equally businesslike and effective.

Selection: Eugene V. Debs, "Industrial and Social Democracy," 73-76 (1916).

Selection: Samuel Gompers, Seventy Years of Life and Labor: An Autobiography, title folio and frontispiece, 97-98, 180-181, 431 (1925).

Questions to Consider

- What does Debs debate in the essay "Industrial and Social Commonwealth"? Why does he oppose private ownership of industry? What is his vision of a just earth? What is the role of education in achieving justice?

- Co-ordinate to these excerpts from Gompers' memoirs, why does he turn down radicalism? How does he portray Socialists? On what grounds does he criticize them?

- What is Gompers' definition of trade unionism?

- What goals does Gompers seem to share with Debs? In what means do they differ?

Selected Sources

John D. Buenker and Joseph Buenker, eds.Encyclopedia of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. 2005.

Chicago Historical Guild and Newberry Library. Encyclopedia of Chicago. www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org.

Leon Fink. "Grade Consciousness American-Style." In In Search of the Working Class: Essays in American Labor History and Political Culture. 1994.

James R. Green. Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the Starting time Labor Movement, and the Bombing That Divided Golden Age America. 2006.

Measuring Worth. Consumer Cost Index [online]. world wide web.measuringworth.com/index.php.

Source: https://dcc.newberry.org/?p=14434

Posted by: barnesweng1974.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Did Workers Respond To The Changing Demands Of The Workplace In The Late Nineteenth Century?"

Post a Comment